Seurat v4 versus v5

2025-03-13

Last updated: 2025-03-13

Checks: 7 0

Knit directory: muse/

This reproducible R Markdown analysis was created with workflowr (version 1.7.1). The Checks tab describes the reproducibility checks that were applied when the results were created. The Past versions tab lists the development history.

Great! Since the R Markdown file has been committed to the Git repository, you know the exact version of the code that produced these results.

Great job! The global environment was empty. Objects defined in the global environment can affect the analysis in your R Markdown file in unknown ways. For reproduciblity it’s best to always run the code in an empty environment.

The command set.seed(20200712) was run prior to running

the code in the R Markdown file. Setting a seed ensures that any results

that rely on randomness, e.g. subsampling or permutations, are

reproducible.

Great job! Recording the operating system, R version, and package versions is critical for reproducibility.

Nice! There were no cached chunks for this analysis, so you can be confident that you successfully produced the results during this run.

Great job! Using relative paths to the files within your workflowr project makes it easier to run your code on other machines.

Great! You are using Git for version control. Tracking code development and connecting the code version to the results is critical for reproducibility.

The results in this page were generated with repository version b8e8e5e. See the Past versions tab to see a history of the changes made to the R Markdown and HTML files.

Note that you need to be careful to ensure that all relevant files for

the analysis have been committed to Git prior to generating the results

(you can use wflow_publish or

wflow_git_commit). workflowr only checks the R Markdown

file, but you know if there are other scripts or data files that it

depends on. Below is the status of the Git repository when the results

were generated:

Ignored files:

Ignored: .Rproj.user/

Ignored: data/1M_neurons_filtered_gene_bc_matrices_h5.h5

Ignored: data/293t/

Ignored: data/293t_3t3_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/293t_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor1_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor1_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor2_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor2_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor3_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor3_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor4_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor4_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/97516b79-8d08-46a6-b329-5d0a25b0be98.h5ad

Ignored: data/Parent_SC3v3_Human_Glioblastoma_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.tar.gz

Ignored: data/brain_counts/

Ignored: data/cl.obo

Ignored: data/cl.owl

Ignored: data/jurkat/

Ignored: data/jurkat:293t_50:50_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/jurkat_293t/

Ignored: data/jurkat_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/pbmc20k/

Ignored: data/pbmc20k_seurat/

Ignored: data/pbmc3k/

Ignored: data/pbmc3k_seurat.rds

Ignored: data/pbmc4k_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/pbmc_1k_v3_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/pbmc_1k_v3_raw_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/refdata-gex-GRCh38-2020-A.tar.gz

Ignored: data/seurat_1m_neuron.rds

Ignored: data/t_3k_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: r_packages_4.4.1/

Untracked files:

Untracked: analysis/bioc_scrnaseq.Rmd

Note that any generated files, e.g. HTML, png, CSS, etc., are not included in this status report because it is ok for generated content to have uncommitted changes.

These are the previous versions of the repository in which changes were

made to the R Markdown (analysis/seurat_v4_vs_v5.Rmd) and

HTML (docs/seurat_v4_vs_v5.html) files. If you’ve

configured a remote Git repository (see ?wflow_git_remote),

click on the hyperlinks in the table below to view the files as they

were in that past version.

| File | Version | Author | Date | Message |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rmd | b8e8e5e | Dave Tang | 2025-03-13 | Author’s recommendation |

| html | 276f7d1 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-13 | Build site. |

| Rmd | d2f9c34 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-13 | Overdispersion varies as a function of abundance |

| html | 7c6077b | Dave Tang | 2025-03-11 | Build site. |

| Rmd | d37908d | Dave Tang | 2025-03-11 | Overdispersion varies across datasets |

| html | d2a2660 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-11 | Build site. |

| Rmd | 4688c40 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-11 | Overdispersion exists in all scRNA-seq datasets if sufficiently sequenced |

| html | 6248d96 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-11 | Build site. |

| Rmd | d47858c | Dave Tang | 2025-03-11 | Pearson residuals |

| html | 747fe3f | Dave Tang | 2025-03-11 | Build site. |

| Rmd | 4aacb58 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-11 | Error versus variance |

| html | fc7e28d | Dave Tang | 2025-03-11 | Build site. |

| Rmd | 6139935 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-11 | Introduction to modelling variance |

| html | 94116b1 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-10 | Build site. |

| Rmd | 4c187b3 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-10 | Data layer |

| html | 0d51a69 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-10 | Build site. |

| Rmd | 48661b3 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-10 | Seurat version 4 vs. 5 |

sctransform

The paper Comparison and evaluation of statistical error models for scRNA-seq is the basis for the default approach used in Seurat version 5. The following is text from the paper:

- Heterogeneity in single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) data is driven by

multiple sources, including biological variation in cellular state as

well as technical variation introduced during experimental processing.

Deconvolving these effects is a key challenge for preprocessing

workflows.

- Separating biological heterogeneity across cells that corresponds to differences in cell type and state from alternative sources of variation represents a key analytical challenge in the normalization and preprocessing of single-cell RNA-seq data.

- Data normalization aims to adjust for differences in cellular sequencing depth, which collectively arise from fluctuations in cellular RNA content, efficiency in lysis and reverse transcription, and stochastic sampling during next-generation sequencing.

- Variance stabilisation aims to address the confounding relationship between gene abundance and gene variance, and to ensure that both lowly and highly expressed genes can contribute to the downstream definition of cellular state.

Using statistical models like Generalised Linear Models:

- Two recent studies proposed to use generalized linear models (GLMs), where cellular sequencing depth was included as a covariate, as part of scRNA-seq preprocessing workflows.

- The sctransform approach utilizes the Pearson residuals from negative binomial regression as input to standard dimensional reduction techniques, while GLM-PCA focuses on a generalized version of principal component analysis (PCA) for data with Poisson-distributed errors.

- More broadly, multiple techniques aim to learn a latent state that captures biologically relevant cellular heterogeneity using either matrix factorization or neural networks, alongside a defined error model that describes the variation that is not captured by the latent space.

If a regression model doesn’t fully explain variability, the residuals might contain structure that another technique can capture to uncover hidden patterns. For example, if a regression model captures main trends, applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on residuals can find underlying structures in the unexplained variance. Another use case can be clustering on residuals to group data points based on deviations from a model.

Parameterising statistical models:

- Likelihood-based approaches require an explicit definition of a statistical error model for scRNA-seq, and there is little consensus on how to define or parameterize this model.

- Multiple groups have utilized a Poisson error model but others argue that the data exhibit evidence of overdispersion, requiring the use of a negative-binomial (NB) distribution.

- Methods that assume a NB distribution have different methods to

parameterize their model.

- A recent study argued that fixing the NB inverse overdispersion parameter \(\theta\) to a single value is an appropriate estimate of technical overdispersion for all genes in all scRNA-seq datasets, while others propose learning unique parameter values for each gene in each dataset.

- This lack of consensus is further exemplified by the scvi-tools suite, which supports nine different methods for parameterizing error models.

- The purpose of this error model is to describe and quantify heterogeneity that is not captured by biologically relevant differences in cell state, and highlights a specific question: How can we model the observed variation in gene expression for an scRNA-seq experiment conducted on a biologically “homogeneous” population?

Error and variance

- Error modeling refers to capturing and understanding the uncertainty, randomness, and deviations in data or predictions. Error is not exactly synonymous with variance but they are related.

- Errors arise from:

- Randomness: unavoidable variability in data, e.g., measurement noise and natural fluctuations

- Model Imperfections: due to missing information or incorrect model assumptions.

- Statistical models, like regression, often include an error term \(\epsilon\) to account for these uncertainties:

\[ Y = f(X) + \epsilon \]

where \(\epsilon\) captures random fluctuations or unknown influences.

While error contributes to variance, they are distinct:

- Error: The deviation of an observation from the model’s predicted value.

- Variance: A statistical measure of how much values deviate from their mean (spread of data).

Errors can be random (causing variability) or systematic (bias), but variance is a quantification of dispersion.

- In regression, we separate variance into explained variance (by the model) and unexplained variance (error).

- Error variance \(\sigma^2\) is modeled to improve predictions and uncertainty estimation.

- For a negative binomial regression model, the Pearson residual \(r_i\) for observation \(i\) is given by:

\[ r_i = \frac{y_i - \hat{y}_i}{\sqrt{\text{Var}(y_i)}} \]

where:

* \(y_i\) = observed count

* \(\hat{y}_i\) = predicted mean

(expected value under the model)

* \(\text{Var}(y_i)\) = model-estimated

variance of \(y_i\)

- Unlike Poisson regression (where \(\text{Var}(y) = \hat{y}\)), the negative binomial model accounts for overdispersion using a dispersion parameter \(\theta\), and the variance is:

\[ \text{Var}(y_i) = \hat{y}_i + \frac{\hat{y}_i^2}{\theta} \]

This means the variance grows faster than the mean, making negative binomial regression suitable when count data has extra variability.

- Pearson residuals can be used for:

- Standardized measure - Large residuals (\(|r_i| > 2\)) may indicate poor model fit.

- Overdispersion check - If Pearson residuals systematically increase with predicted values, it suggests the model may not fully account for overdispersion.

- Model diagnostics - Residual plots help assess whether assumptions (e.g., correct functional form) hold.

Pearson residuals focus on variance-adjusted differences and deviance residuals come from likelihood-based goodness-of-fit measures. They both help diagnose model fit, but deviance residuals tend to emphasise extreme deviations more. Pearson residuals in negative binomial regression are useful for model diagnostics, particularly for checking overdispersion and assessing fit.

Variance stabilisation

- Variance stabilisation is a statistical transformation technique used to make the variance of a dataset independent of the mean.

For example in the linked paper:

A negative binomial error model with \(\theta\) = 100 resulted in clear heteroskedasticity in multiple datasets, as we observed a strong relationship between the mean expression of a gene, and its residual variance.

Therefore relationship between expression and variance means heteroskedasticity, which means variance stabilisation is required.

- In many biological datasets, including scRNA-seq, the variance of

gene expression measurements often increases with the mean

expression level.

- This heteroskedasticity (non-constant variance) can obscure downstream analyses such as clustering, differential expression testing, or dimensionality reduction.

- The goal of variance stabilisation is to transform the data so that the variance becomes roughly constant across different levels of the mean, i.e., to achieve homoskedasticity.

Some methods for variance stabilisation:

- Logarithmic transformation:

- Common when variance increases with the mean.

- Applied as:

log(x + c)(wherecis a pseudocount to handle zeros). - Effective when variance increases linearly with the mean.

- Square-root transformation:

- Applied as:

sqrt(x), often used for Poisson-distributed data. - Suitable when variance is proportional to the mean.

- Applied as:

- Variance Stabilising Transformation (VST):

- Involves estimating the mean-variance relationship and applying a transformation derived from it.

- Regularised methods:

- Uses negative binomial regression to model and normalise gene expression, accounting for sequencing depth and technical noise.

- Produces a Pearson residual that approximates homoskedastic behavior.

Seurat object

Import raw pbmc3k dataset from my server.

seurat_obj <- readRDS(url("https://davetang.org/file/pbmc3k_seurat.rds", "rb"))

seurat_objAn object of class Seurat

32738 features across 2700 samples within 1 assay

Active assay: RNA (32738 features, 0 variable features)

1 layer present: countsFilter.

pbmc3k <- CreateSeuratObject(

counts = seurat_obj@assays$RNA$counts,

min.cells = 3,

min.features = 200,

project = "pbmc3k"

)

pbmc3kAn object of class Seurat

13714 features across 2700 samples within 1 assay

Active assay: RNA (13714 features, 0 variable features)

1 layer present: countsSeurat workflows

Process with the Seurat 4 workflow.

seurat_wf_v4 <- function(seurat_obj, scale_factor = 1e4, num_features = 2000, num_pcs = 30, cluster_res = 0.5, debug_flag = FALSE){

seurat_obj <- NormalizeData(seurat_obj, normalization.method = "LogNormalize", scale.factor = scale_factor, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj <- FindVariableFeatures(seurat_obj, selection.method = 'vst', nfeatures = num_features, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj <- ScaleData(seurat_obj, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj <- RunPCA(seurat_obj, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj <- RunUMAP(seurat_obj, dims = 1:num_pcs, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj <- FindNeighbors(seurat_obj, dims = 1:num_pcs, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj <- FindClusters(seurat_obj, resolution = cluster_res, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj

}

pbmc3k_v4 <- seurat_wf_v4(pbmc3k)Warning: The default method for RunUMAP has changed from calling Python UMAP via reticulate to the R-native UWOT using the cosine metric

To use Python UMAP via reticulate, set umap.method to 'umap-learn' and metric to 'correlation'

This message will be shown once per sessionpbmc3k_v4An object of class Seurat

13714 features across 2700 samples within 1 assay

Active assay: RNA (13714 features, 2000 variable features)

3 layers present: counts, data, scale.data

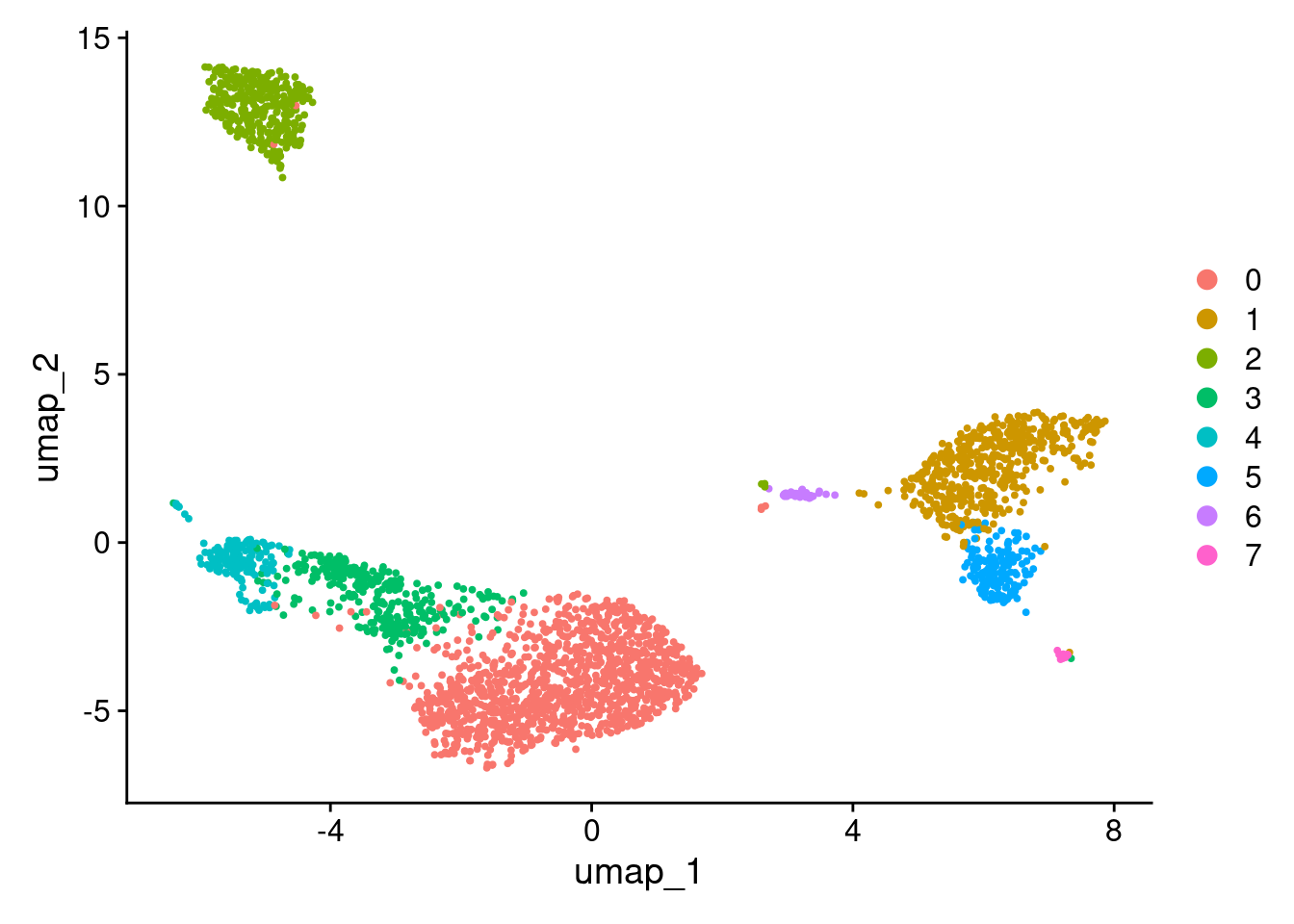

2 dimensional reductions calculated: pca, umapUMAP.

DimPlot(pbmc3k_v4, reduction = "umap")

| Version | Author | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 0d51a69 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-10 |

seurat_wf_v5 <- function(seurat_obj, scale_factor = 1e4, num_features = 2000, num_pcs = 30, cluster_res = 0.5, debug_flag = FALSE){

seurat_obj <- SCTransform(seurat_obj, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj <- RunPCA(seurat_obj, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj <- RunUMAP(seurat_obj, dims = 1:num_pcs, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj <- FindNeighbors(seurat_obj, dims = 1:num_pcs, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj <- FindClusters(seurat_obj, resolution = cluster_res, verbose = debug_flag)

seurat_obj

}

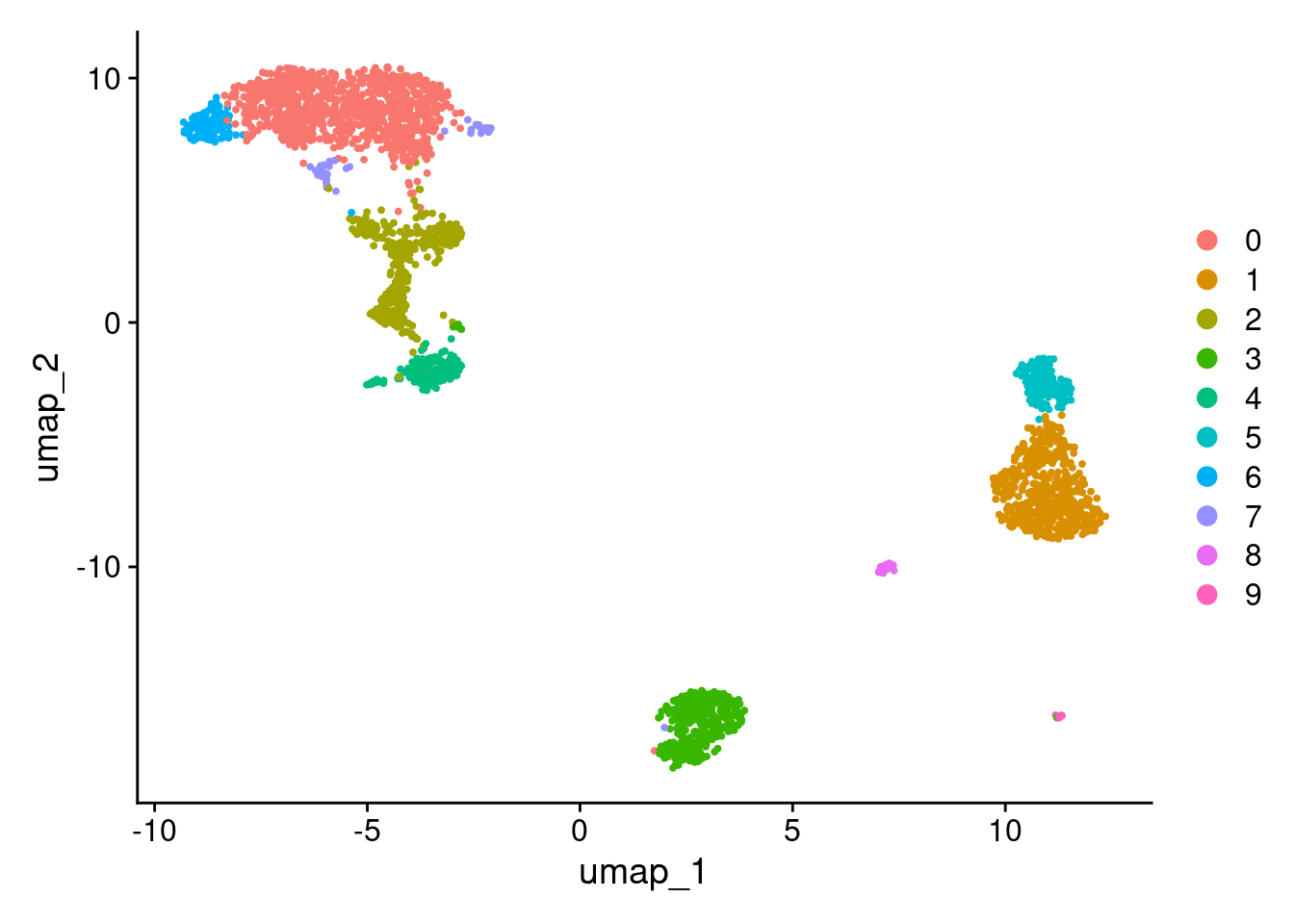

pbmc3k_v5 <- seurat_wf_v5(pbmc3k)

pbmc3k_v5An object of class Seurat

26286 features across 2700 samples within 2 assays

Active assay: SCT (12572 features, 3000 variable features)

3 layers present: counts, data, scale.data

1 other assay present: RNA

2 dimensional reductions calculated: pca, umapUMAP.

DimPlot(pbmc3k_v5, reduction = "umap")

| Version | Author | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 0d51a69 | Dave Tang | 2025-03-10 |

Data layer

Version 4 store log normalised data.

colSums(pbmc3k_v4@assays$RNA$data)[1:6]AAACATACAACCAC-1 AAACATTGAGCTAC-1 AAACATTGATCAGC-1 AAACCGTGCTTCCG-1

1605.823 2027.859 2040.169 1902.960

AAACCGTGTATGCG-1 AAACGCACTGGTAC-1

1388.125 1653.061 The data layer is in the SCT assay.

colSums(pbmc3k_v5@assays$SCT$data)[1:6]AAACATACAACCAC-1 AAACATTGAGCTAC-1 AAACATTGATCAGC-1 AAACCGTGCTTCCG-1

786.2686 1024.4731 1029.3032 934.4454

AAACCGTGTATGCG-1 AAACGCACTGGTAC-1

666.1142 764.8101 Compare clustering

More granular clustering of version 4’s cluster 0 in version 5.

stopifnot(all(row.names(pbmc3k_v4@meta.data) == row.names(pbmc3k_v5@meta.data)))

table(

pbmc3k_v4@meta.data$seurat_clusters,

pbmc3k_v5@meta.data$seurat_clusters

)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

0 970 0 71 2 0 0 100 44 0 0

1 0 479 0 0 0 9 0 0 3 0

2 1 0 0 349 0 0 0 1 0 0

3 4 0 290 1 5 0 0 1 0 0

4 0 0 5 6 152 0 0 0 0 0

5 0 16 0 0 0 145 0 0 0 0

6 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 31 0

7 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 12Appendix

More text from the paper Comparison and evaluation of statistical error models for scRNA-seq.

Shallow sequencing masks overdispersion in scRNA-seq data

- The rationale behind a Poisson model assumes that homogeneous cells express mRNA molecules for a given gene at a fixed underlying rate, and the variation in scRNA-seq results specifically from a stochastic sampling of mRNA molecules, for example due to inefficiencies in reverse transcription and PCR, combined with incomplete molecular sampling during DNA sequencing

- While the Poisson distribution is well suited to capture variation

driven by stochastic technical loss and sampling noise, it cannot

capture other sources of biological heterogeneity between cells that are

not driven by changes in cell state, for example, intrinsic variation

caused by stochastic transcriptional bursts.

- These fluctuations would cause scRNA-seq data to deviate from Poisson statistics, exhibiting overdispersion.

- To assess whether scRNA-seq datasets follow the Poisson distribution, the authors performed a goodness-of-fit test, independently modeling the observed counts for each gene to be Poisson distributed, while accounting for differences in sequencing depth between individual cells.

- In each of the 59 datasets analysed, genes exhibiting Poisson

variation were overwhelmingly lowly expressed compared to genes that

were overdispersed.

- Moreover, when comparing results for cell-line datasets where we expect low levels of variation in cell state, we found that the global fraction of genes deviating from a Poisson distribution was correlated with the average sequencing depth of the dataset.

- The results suggest that scRNA-seq datasets commonly exhibit biological variation that exceeds Poisson sampling, but that the statistical power to detect these fluctuations requires sufficient sequencing depth.

- After downsampling, only 0.5% genes failed the Poisson goodness-of-fit test, demonstrating that reducing cellular sequencing depth can artificially create the appearance of Poisson variation.

- The authors conclude that the Poisson error model may represent an acceptable approximation for scRNA-seq datasets with shallow sequencing, but as the sensitivity of molecular profiling continues to increase, error models that allow for overdispersion are required for scRNA-seq analysis.

The level of overdispersion varies substantially across datasets

- Recent work suggested that a negative binomial model with a fixed parameterisation (for example, inverse overdispersion parameter \(\theta\)=100) could be applied to all scRNA-seq datasets to achieve effective variance stabilisation.

- To explore whether a single value of \(\theta\) could be applied to diverse scRNA-seq datasets, we first independently fit \(\theta\) estimates for each gene in each dataset using a GLM with negative binomial errors (NB GLM), using library size as an offset to account for variation in cellular sequencing depth.

- Substantial differences were observed in the magnitude of the

estimated \(\theta\) across different

datasets, though replicate datasets from the same study yielded

concordant results.

- Consistent with previous results \(\theta\) values for each dataset varied across different biological systems, technologies, and sequencing depths.

- To consider different methods for NB parameterisation, we first tested the ability for a single value of \(\theta\) to perform effective variance stabilization across a range of datasets.

- Processed 59 datasets using an NB GLM after fixing \(\theta\) to a single value for all genes in

the dataset (for example, \(\theta\)=100).

- Found that no single value of \(\theta\) could achieve effective variance stabilisation across all datasets.

- Concluded that fixing a single value of \(\theta\) may achieve effective performance in certain cases, but is unlikely to generalise across the diversity of systems and technologies represented by scRNA-seq data.

Gene overdispersion varies as a function of abundance

- An alternative strategy for parameterizing \(\theta\) leverages a well-characterized strategy for modeling counts in bulk RNA-seq data, where per-gene dispersion estimates have repeatedly been found to vary as a function of expression abundance.

- In sctransform, we aim to estimate a global relationship between

gene abundance and \(\theta\) by

employing a regularization (i.e., preventing overfitting) procedure

where parameters are first fit for each gene individually, but

information from genes with similar average abundances is subsequently

pooled together in order to improve the robustness of parameter

estimates.

- The underlying rationale for this choice is the non-decreasing relationship between gene abundance and \(\theta\) that has been repeatedly observed in bulk RNA-seq studies.

- When analyzing each of the technologies and biological systems explored in this manuscript, we identified the same global patterns relating gene abundance and overdispersion levels.

- Considered the finding that \(\theta\) values should not vary as a function of gene abundance, and suggested that the relationship between these two variables was driven entirely by biases in the parameter estimation procedure, especially when analyzing lowly expressed genes.

- Confirmed that lowly expressed genes, particularly those with

average abundance <0.1 UMI/cell, posed difficulties for parameter

estimation. This is because the vast majority of count values for these

genes are 0, creating inherent challenges in maximum likelihood

estimation.

- When estimating parameters on simulated data drawn from a negative binomial with fixed \(\theta\), confirmed a bias for these genes that resulted in decreased parameter estimates for \(\theta\).

- However, using two complementary analyses, found that this bias was

not sufficient to explain the true relationships we observed in

biological data.

- First, observed a non-decreasing relationship between gene abundance (\(\mu\)) and dispersion (\(\theta\)) even when moving beyond the threshold for lowly expressed genes, which we did not observe when analyzing simulated data.

- Additionally, we attempted to increase (“upsample”) the depth of single cell datasets by pooling together molecular counts from cells with similar molecular profiles as inspired by the MetaCell framework. We repeated the parameter estimation procedure on metacells generated either from single-cell data, or using our simulation framework. Increasing the depth of sampling removed the effects of bias when analyzing simulated data, but preserved the observed relationship between \(\mu\) and \(\theta\) on real biological datasets.

- Concluded that when modeling scRNA-seq data using a negative binomial distribution, the inverse overdispersion parameter \(\theta\) does vary as a function of gene abundance, but the true nature of this relationship can be masked for genes with low molecular counts.

Recommendations for modeling heterogeneity in scRNA-seq datasets

- The findings highlight how the extensive diversity of scRNA-seq datasets poses challenges in identifying uniform procedures for the preprocessing and normalization of scRNA-seq data.

- Sparsely sequenced datasets may appear to be compatible with the use of Poisson error models, but datasets with additional sequencing depth reveal clear evidence of overdispersion.

- The level of overdispersion, exemplified by the NB parameter \(\theta\), also can vary substantially

across datasets, technologies, and systems and even varies within a

dataset as a function of gene abundance.

- However, the estimation of robust parameter estimates for \(\theta\) can be challenging for lowly expressed genes, especially when analyzing datasets with sparse sequencing.

- The authors therefore considered recommendations for balancing these considerations, providing the flexibility to learn error models that can be robustly applied to our full spectrum of scRNA-seq datasets.

The first recommendation is to use the negative binomial observation model as an alternative to the Poisson distribution.

- Their analyses show that the Poisson distribution is a reasonable approximation for technical-control datasets consisting of endogenous or spike-in RNA, as well as for some scRNA-seq experiments with shallow sequencing.

- However, scRNA-seq datasets from cell lines exhibit clear evidence of overdispersion at higher sequencing depths, even for genes that do not correlate with changes in cell type or state.

- At least some of this overdispersion likely originates from “intrinsic” noise, stochastic cellular variation that is inherent to the processes of mRNA transcription and degradation, and will affect the expression heterogeneity of all genes.

- While this variation is not a result of measurement error, it is not the primary focus of downstream scRNA-seq analyses, including the identification of cell types and states, and the inference of developmental trajectories.

- We therefore recommend that this variation be modeled independently of the latent space, which requires the use of a negative binomial error model.

- We note that the Poisson distribution is a special case of the negative binomial, and therefore the NB model can be successfully applied for datasets with very shallow sequencing, with appropriate parameter settings.

The second recommendation is to learn negative binomial parameters separately for each dataset, rather than fixing them to a single value across all analyses. Moreover, they recommend allowing \(\theta\) to vary across genes within a dataset, as a function of average gene abundance.

- The relationship between \(\mu\) and \(\theta\) has been repeatedly demonstrated in bulk RNA-seq and is apparent across diverse scRNA-seq datasets as well, particularly for genes with sufficient sequencing depth.

- Using a fixed \(\theta\) to parameterize all genes in a scRNA-seq dataset leads to ineffective variance stabilization and results in a global relationship between expression level and expression variance.

- Results highlighted that lowly expressed genes with particularly

sparse molecular counts often lacked sufficient information content to

robustly detect overdispersion.

- The authors therefore designed a modified regularization procedure for learning GLM parameter estimates and calculating Pearson residuals.

- First, the authors fix the slope of the NB GLM to its analytically derived solution of \(ln(10)\), so that only the overdispersion and intercept parameters are estimated for each gene.

- Second, for genes with very low expression (\(\mu<0.001\)), or where the variance of their molecular counts does not exceed the mean (i.e., \(\sigma^2 \le \mu\)), we do not have sufficient evidence for overdispersion to fit negative binomial parameters. We therefore removed these genes from the regularization process and fixed their \(\theta\) parameter to \(\infty\), exemplifying a Poisson distribution.

- The authors found that their modified regularization enables them to reproducibly learn gene-specific parameters even when using a subset of cells in the estimation procedure.

- Third, they apply a lower bound on the minimum variance while calculating the Pearson residual for each per cell to prevent genes with minimal information content from resulting in high residual variance. In particular, this step helps to ensure that very low UMI counts (i.e., 1 to 2 molecules) are not assigned extremely high Pearson residuals.

- All this work has been implemented in the updated regularization procedure as a version 2 update of sctransform (sctransform v2).

sessionInfo()R version 4.4.1 (2024-06-14)

Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

Running under: Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS

Matrix products: default

BLAS: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/openblas-pthread/libblas.so.3

LAPACK: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/openblas-pthread/libopenblasp-r0.3.20.so; LAPACK version 3.10.0

locale:

[1] LC_CTYPE=en_US.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C

[3] LC_TIME=en_US.UTF-8 LC_COLLATE=en_US.UTF-8

[5] LC_MONETARY=en_US.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=en_US.UTF-8

[7] LC_PAPER=en_US.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C

[9] LC_ADDRESS=C LC_TELEPHONE=C

[11] LC_MEASUREMENT=en_US.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

time zone: Etc/UTC

tzcode source: system (glibc)

attached base packages:

[1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

other attached packages:

[1] Seurat_5.2.1 SeuratObject_5.0.2 sp_2.2-0 lubridate_1.9.4

[5] forcats_1.0.0 stringr_1.5.1 dplyr_1.1.4 purrr_1.0.4

[9] readr_2.1.5 tidyr_1.3.1 tibble_3.2.1 ggplot2_3.5.1

[13] tidyverse_2.0.0 workflowr_1.7.1

loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

[1] RColorBrewer_1.1-3 rstudioapi_0.17.1

[3] jsonlite_1.9.1 magrittr_2.0.3

[5] spatstat.utils_3.1-2 farver_2.1.2

[7] rmarkdown_2.29 zlibbioc_1.52.0

[9] fs_1.6.5 vctrs_0.6.5

[11] ROCR_1.0-11 DelayedMatrixStats_1.28.1

[13] spatstat.explore_3.3-4 S4Arrays_1.6.0

[15] htmltools_0.5.8.1 SparseArray_1.6.2

[17] sass_0.4.9 sctransform_0.4.1

[19] parallelly_1.42.0 KernSmooth_2.23-24

[21] bslib_0.9.0 htmlwidgets_1.6.4

[23] ica_1.0-3 plyr_1.8.9

[25] plotly_4.10.4 zoo_1.8-13

[27] cachem_1.1.0 whisker_0.4.1

[29] igraph_2.1.4 mime_0.12

[31] lifecycle_1.0.4 pkgconfig_2.0.3

[33] Matrix_1.7-0 R6_2.6.1

[35] fastmap_1.2.0 GenomeInfoDbData_1.2.13

[37] MatrixGenerics_1.18.1 fitdistrplus_1.2-2

[39] future_1.34.0 shiny_1.10.0

[41] digest_0.6.37 colorspace_2.1-1

[43] S4Vectors_0.44.0 patchwork_1.3.0

[45] ps_1.9.0 rprojroot_2.0.4

[47] tensor_1.5 RSpectra_0.16-2

[49] irlba_2.3.5.1 GenomicRanges_1.58.0

[51] labeling_0.4.3 progressr_0.15.1

[53] spatstat.sparse_3.1-0 timechange_0.3.0

[55] httr_1.4.7 polyclip_1.10-7

[57] abind_1.4-8 compiler_4.4.1

[59] withr_3.0.2 fastDummies_1.7.5

[61] MASS_7.3-60.2 DelayedArray_0.32.0

[63] tools_4.4.1 lmtest_0.9-40

[65] httpuv_1.6.15 future.apply_1.11.3

[67] goftest_1.2-3 glmGamPoi_1.18.0

[69] glue_1.8.0 callr_3.7.6

[71] nlme_3.1-164 promises_1.3.2

[73] grid_4.4.1 Rtsne_0.17

[75] getPass_0.2-4 cluster_2.1.6

[77] reshape2_1.4.4 generics_0.1.3

[79] gtable_0.3.6 spatstat.data_3.1-4

[81] tzdb_0.4.0 data.table_1.17.0

[83] hms_1.1.3 XVector_0.46.0

[85] BiocGenerics_0.52.0 spatstat.geom_3.3-5

[87] RcppAnnoy_0.0.22 ggrepel_0.9.6

[89] RANN_2.6.2 pillar_1.10.1

[91] spam_2.11-1 RcppHNSW_0.6.0

[93] later_1.4.1 splines_4.4.1

[95] lattice_0.22-6 survival_3.6-4

[97] deldir_2.0-4 tidyselect_1.2.1

[99] miniUI_0.1.1.1 pbapply_1.7-2

[101] knitr_1.49 git2r_0.35.0

[103] gridExtra_2.3 IRanges_2.40.1

[105] SummarizedExperiment_1.36.0 scattermore_1.2

[107] stats4_4.4.1 xfun_0.51

[109] Biobase_2.66.0 matrixStats_1.5.0

[111] UCSC.utils_1.2.0 stringi_1.8.4

[113] lazyeval_0.2.2 yaml_2.3.10

[115] evaluate_1.0.3 codetools_0.2-20

[117] cli_3.6.4 uwot_0.2.3

[119] xtable_1.8-4 reticulate_1.41.0

[121] munsell_0.5.1 processx_3.8.6

[123] jquerylib_0.1.4 GenomeInfoDb_1.42.3

[125] Rcpp_1.0.14 globals_0.16.3

[127] spatstat.random_3.3-2 png_0.1-8

[129] spatstat.univar_3.1-2 parallel_4.4.1

[131] dotCall64_1.2 sparseMatrixStats_1.18.0

[133] listenv_0.9.1 viridisLite_0.4.2

[135] scales_1.3.0 ggridges_0.5.6

[137] crayon_1.5.3 rlang_1.1.5

[139] cowplot_1.1.3